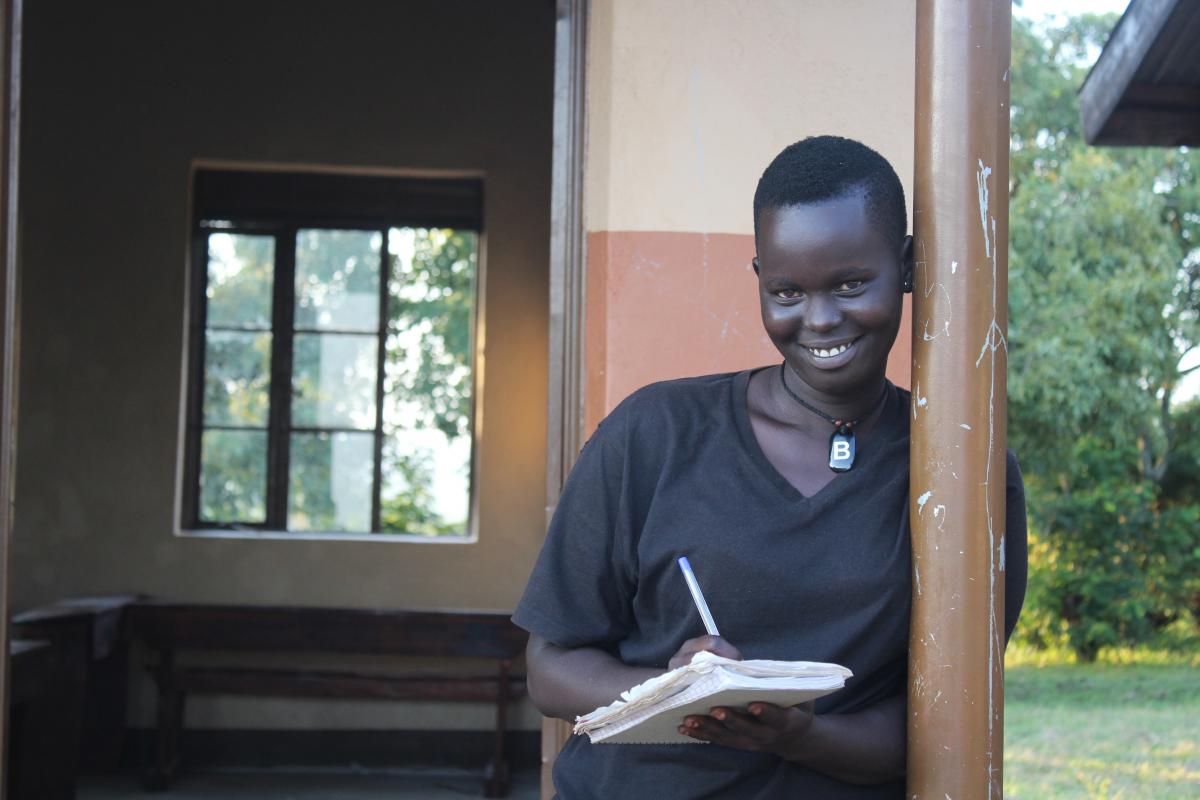

School girl aspires to become midwife to help pregnant refugee women

The sun is setting on the horizon, casting a soft orange

light on the trees lining the compound of Lokopio Primary School in Bidibidi

refugee settlement, Northern Uganda.

Children stream out of one particular classroom. Their school

mates left one and a half hours ago but the Primary Seven class, which is

preparing for their Primary Leaving Examinations, stayed on for revision, just

like they have done every day for the past few months.

Clutching her books, 18-year-old Susan Sadia, a refugee from

South Sudan, readies herself for the long walk home, a journey that will take

her about 40 minutes.

“I am reading hard so I can become a midwife,” she says. “I

want to help the pregnant women suffering in the settlement, especially those

who did not come to Uganda with their husbands.”

Sadia knows only too well the suffering that refugee women

endure. In 2016, she fled fighting in South Sudan with her aunt, cousins and

siblings. The journey to safety in Uganda, on foot, across four rivers, some of

which did not have bridges, took three days from their home in Yei. Besides the

few belongings balancing on her head, Sadia had to carry her three-year-old

brother on her back. Her mother had refused to leave South Sudan.

Although she had been in

school in South Sudan, in 2017 Sadia did not attend school in Uganda. Bidibidi,

where she stays, is the largest refugee settlement in the country, hosting

about 272,000 refugees, mainly from South Sudan.

As with all other services,

refugees have to share education facilities with the Ugandan nationals. Uganda

recently launched an Education Response

Plan for Refugees and Host Communities, against a backdrop of inadequate

education services for children in those communities.

According to the Plan,

the number of children in refugee settlements far overrides the available

schools, teachers and learning materials. In Bidibidi

settlement, for instance, the pupil teacher ratio is 94:1, compared to a

national average of 43:1.

Sadia’s fate took a turn for the better in 2018. With funding

from the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, Save the Children, an

NGO, started the Accelerated Learning Programme. This is a catch-up programme

that uses a compressed curriculum, over three years, to enable children who had

dropped out of school to re-enroll. It is run within existing primary schools.

Sadia

is on the final year and has the opportunity to do the Uganda Primary Leaving

Examinations which, she hopes, will be her ticket to secondary school and

ultimately her dream of becoming a midwife.

“I have seen pregnant women deliver from home because there

is no one to help them. No husband to take them to the health centre,” she

says. “When I become a midwife I will educate women on the need to go to a health

centre to give birth, because that is where you find doctors and midwives who

can help.”

Sadia’s optimism belies the challenges she faces in the

pursuit of her dream. The school does not offer meals for children, so those

who stay nearby go home for lunch. “My home is far – I cannot afford to make

the journey, so I only eat in the evening,” she says.

Sometimes Sadia misses school because she has to take care

of the home when her aunt, who sells food in the market, travels to stock up

for her stall. She makes up for lost time by revising at night, efforts that

are sometimes hampered by the lack of electricity in the settlement. The

family’s solar lamp is now worn out and operates intermittently.

But she is determined to pass her examinations, drawing

inspiration from her family.

“My parents did not go to school, so I want to be

different. If I get a good education I will be able to help my family,” she

says.

With this determination, the women of Bidibidi, and later

South Sudan, will be fortunate to get such a passionate midwife.

Latest news from this project

No news