Strengthening coordination in the supply and demand of aid to Mozambique’s energy sector

Strengthening coordination

in the supply and demand of aid to Mozambique’s energy sector

By E.Waeterloos and A.Van de Velde, Enabel Mozambique

Over the past years the energy

sector in Mozambique has gone through various transitions. This changing

context has created new challenges and affected the responsibilities, needs and

resources of key stakeholders. With various new donors providing assistance to

the energy sector, possible overlaps and complementarities need to be reconsidered.

Enabel supports some of Mozambique’s most important governmental actors to build

their institutional and operational capacity and to stimulate complementarity, coordination

and even division of labour[1]

among international and local stakeholders.

An evolving sector

End 2017, HE E.M. Tonela was appointed

as new Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy. As economist and previous

board member of the Hidroelectrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB), Mr. Tonela brings

expertise from the private energy sector. In December 2017, the new Energy

Regulatory Authority (ARENE) replaced the previous advisory CNELEC and is now responsible

for the supervision and regulation of production, transport, distribution,

commercialization and storage of electricity from any source of energy. Moreover,

in 2018 a range of new energy polices has been developed. The adoption of the National Electrification

Strategy (ENE) was an important step in Mozambique’s strategy to achieve

universal access to electricity by 2030 and clearly identifies the three main

challenges in achieving this: institutional (lack of planning and

coordination), financial (operating and connecting costs) and technical

(reliability of the system). In October 2018, the Mozambican government also

approved the Integrated Master Plan for electricity infrastructure. It is an

ambitious plan aimed at increasing the country’s capacity to generate, consume

and export electricity over the next quarter of a century. Furthermore, the

Electricity Law of 1997 is under revision and aims to promote the efficiency of

the electricity sector, encourage greater participation of the private sector

and establish tariff mechanisms. Lastly, the discovery of immense natural gas and

oil reserves a decade ago may improve the country’s macro-economic situation

and living standards of the population, but at the same time triggered poor

government decisions leading to an accumulation of unsustainable levels of debt

(secret loans) and strained donor relations. In short, the energy sector in

Mozambique evolves in different dimensions in terms of supply and demand of

renewable and non-renewable energy. These changes lead to a situation in which

the various key national and international stakeholders need to adapt to their

new roles and set up better coordination mechanisms.

Surveying aid supply and demand in the sector

The technical assistance provided

through Enabel’s capacity building project “CB MIREME” supports the Ministry of

Mineral Resources and Energy (MIREME), its provincial directorates (DIPREME)

and ARENE to cope better with their new role, responsibilities and the changing

context. Early in 2018, MIREME formulated an urgent demand through the Energy

Sector Working Group (ESWG) - the donor-government policy dialogue and

interface platform - to obtain an updated overview of donor activities and

commitments in the electric energy sector and to explore possibilities for

better coordination. Enabel collected data through a structured questionnaire between

the 14th of June and the 23rd of July 2018. Through the ESWG,

22 potential donors were contacted of which more than half (14) eventually responded.

The objective of this snap survey is to improve planning, alignment, and coordination

between the Mozambican government, donors, and other key partners. A

preliminary analysis was presented at the donor coordination meeting on the 5th

of July 2018, organized and financed by Enabel in collaboration with MIREME and

ESWG. This brief summarizes the most important findings of the final analysis.

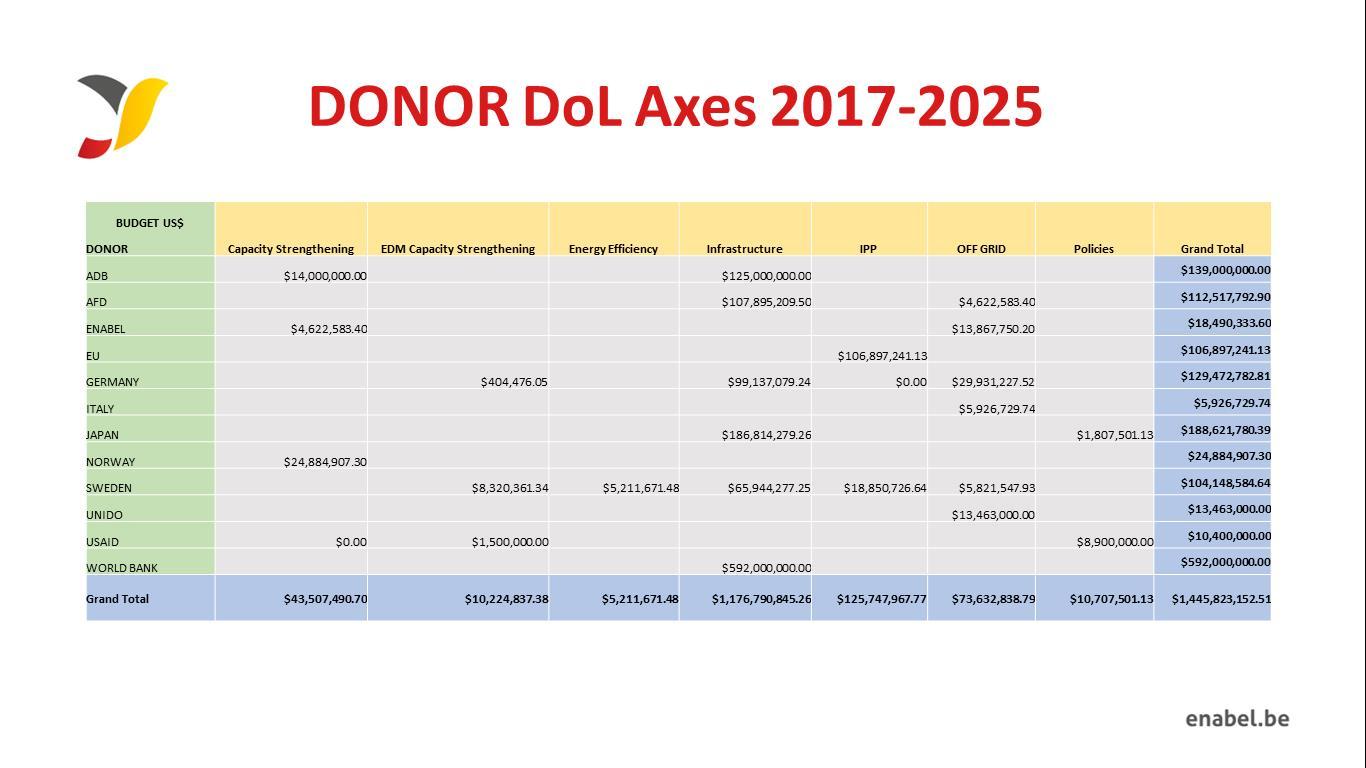

For the period 2017 to

2025, 12 donors reported 45 projects earmarked for Mozambique’s energy sector

with a total reported financial supply of almost US$ 1.5 billion. Twenty five

projects are already operational, while 19 have not yet been signed and are

still in the pipeline. This means that with an equivalent of almost US$ 900

million, the majority of funding between 2017 and 2025 is not yet formally

committed. These donor interventions are situated in a variety of areas, with investment

in grid infrastructure (US$1.2 billion) and the promotion of independent power

producers (IPP) (US$ 126 million) as frontrunners. The other intervention areas

are in order of importance: promotion of off-grid technologies, general

capacity strengthening of the sector’s actors, capacity strengthening of the government-owned

utility responsible for generation, transmission and distribution of

electricity through the national grid EDM, support to the development of sector

policies and strategies, and the promotion of energy efficiency. Sweden has the

most diverse portfolio with 10 projects in five of the seven intervention areas

and is the main sponsor of capacity strengthening in EDM, as well as the only donor investing in

energy efficiency. The World Bank on the other hand, invests its entire budget in

four projects of building grid infrastructure, while the EU focuses solely on

the promotion of independent power producers. Norway is the biggest investor in

the area of the sector’s general capacity strengthening, while Germany is the donor

with the biggest investments in the off-grid axis; USAID focuses mainly on

policies. The general pattern of flow of funds shows a peak in 2019 – 2020 (US$

215 - 261 million) but no commitments planned after 2023.

As to the demand side

of aid, the data collected from donors does not allow an analysis of each and

every recipient individually. The importance of energy actors in terms of donor

funds received can, however, be determined through an approximation. A donor can

reach several recipients in one single intervention. Therefore, the only

approximation of funds channelled to individual recipients possible is by allocating

each and every time the project’s total financial volume to each recipient listed

in an intervention. Such cumulating of funds obviously results in double

counting in absolute terms, but provides at least a relative weight of every

recipient in the total energy sectors’ funding basket. This can be explained by

the case of EDM: EDM receives the highest financial attention between 2017-25,

both in absolute terms where at least US$ 654 million are directly foreseen for

EDM, as in relative terms, where donor projects which support (among others) EDM

cumulatively amount to US$ 1.3 billion out of a cumulative US$ 2.6 billion. In

the same approximation, projects which support the private sector combine to a

total of US$ 400 million. In relative perspective, FUNAE and MIREME both get

considerably less attention (respectively US$ 233 million and 260 million).

However, it is especially remarkable that the new energy regulator ARENE, civil

society and provincial MIREME directorates (DIPREME) receive less than 2% of

the approximation’s total funding volume

of US$ 2.6 billion.

Challenges to coordination in and between aid supply and demand

Even though this

snap survey lacks detail to identify the exact volume of funds channelled to

individual recipients or to highlight overlaps and conflicts between project

activities and funds, it does provide a first range of pointers on how to improve

coordination among and between donors and recipients. For example, geographical

coverage of funding is unequal, with provinces of Maputo, Inhambane and Gaza

receiving most project funding and Sofala, Cabo Delgado and Niassa the least. Similar

funding inequalities apply to recipient partners (EDM versus ARENE for

instance) and intervention areas (grid infrastructure versus energy efficiency).

Such analysis can further inform discussions on improved coordination and

alignment. The information needs to be

further refined in order to fully support discussions on overlaps, conflicts,

complementarity and division of labour (DoL). The survey should have a wider

coverage and reach out to traditional as well as new donors, include details on

aid modalities (e.g. loan or grant), engage in in-depth interviews with each

donor to determine overlaps and improved DoL, and triangulate and harmonize

information with MIREME and EDM data. It is therefore Enabel’s recommendation

to continue in 2019 with more formal and systematic half-yearly information

gathering and data management under supervision of, for instance, a team comprising

members of the Energy Sector Working Group, MIREME and EDM. Such panel survey complemented

with more qualitative in-depth information can support discussions within

government and within the ESWG on improved alignment and coordination between and

among aid supply and demand.

[1] Division

of labour (DoL) aims at reducing fragmentation of aid by stimulating

coordination and harmonisation among donors, who often concentrate on the same

countries and sectors.

Laatste nieuws van dit project

Geen nieuws